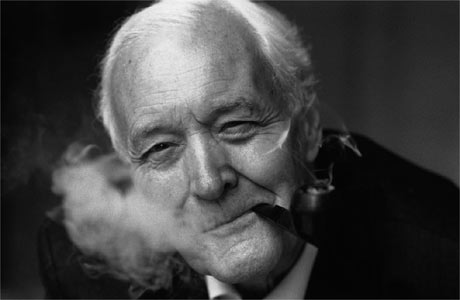

An Inspiration to the end

Karl Marx (died 14th March 1883.) Tony Benn ( died 14th March 2014)

Both were inspirations for humanity. So many of us feel Tony Benn was a hero in our lifetime. CJ Stone’s interview with Tony Benn certainly provides us with food for thought. The media will no doubt seek to demonise him yet again as they seek to preserve a world where the few benefit at the expense of the many. His legacy will not be forgotten.

An Interview with Tony Benn by C J Stone

The following interview was recorded on the 9th October 2000 at Tony Benn’s house in Notting Hill. It was for a book I was planning to write at the time, called The Lords of Misrule about the protest movement, which had recently scored such a high-profile victory by closing down the WTO meeting in Seattle in 1999. The interview was published in Red Pepper and on the LabourNet website. I put in up here today as a tribute to Tony Benn, one of the few honest politicians, who died on the 14th March 2014. An inspiration to the end.

Tony Benn: I’ll just mark this. It is now the ninth of October the year 2000. I’m with Chris Stone who was coming to see me about protest but might be something else. OK, I’m with you.

Chris Stone: Really it’s about the current globalisation project. So. There’s a whole range of things I want to ask you really. First of all, what do you understand by the term “globalisation”?

TB: It’s the free movement of capital, but not the free movement of labour. It’s imperialism under a new form: only the agents of imperialism are companies rather than countries. But of course the companies are supported by countries. So America backs up its oil companies by going to war where there’s an oil interest, as we did in the Falklands, because the Falklands was an oil war, there’s more oil around the Falklands than there is around the United Kingdom, and that’s what that was about. And of course some companies are now bigger than nation states. Ford is bigger than South Africa. Toyota is bigger than Norway. And some of these big guys come and dominate the world, bring pressure to bear on governments, and to make sure they then buy both parties in Britain and America, and then expect to pay off which ever one wins. And imperialism of course is coming back now. And it really is, I think, a direct counter attack on democracy. The franchise was only extended to one person one vote in 1948 in Britain, and at the age of 18 later even than that, and at that moment the guys at the top got really frightened that the poor could use the vote not just to buy political power, but economic power. So they decided to prevent it. They couldn’t prevent it during the period of the Soviet Union, because the existence of an anti-capitalist superpower frightened the life out of the establishment. And so they had to let the colonies go, in case they went communist, concede the welfare state in case western Europe went socialist. Only America is now the dominant power and not Britain, and we’re piggy-backing on the back of American military power. . . .

CS: And we’re doing their dirty work for them. . .

TB: Exactly. And now we can be a superpower but not a super state. . . . like saying I’ll have a banana but not a banana split. Ludicrous. But it’s an indication that the urge for domination is the urge that’s put forward by governments. . . But then they’re all in the pay, or under the control, of corporate finance. I mean it’s really, in a sense it’s a very alarming development. But as long as people understand it, and don’t look for scapegoats like asylum seekers, we might make some progress.

CS: Carrying on from that, about the recent protests in Prague against the World Bank and the IMF: as I understand it, the WB/IMF were originally conceived as humanitarian institutions, that is, to aid development. . .

TB: Well I’ve no doubt they were presented as world development. . .

CS: I suppose the questions is: it’s your insights into how such institutions, which at least put forward a humanitarian front. . .

TB: Everything is humanitarian. I mean, the war, when we used depleted uranium and cluster bombs in Kosovo. And funnily enough, because I was thinking of this word “humanitarian”, I looked up the killing of 11, 000 Sudanese at Omdurman 102 years ago – it happened to be the centenary of the bombing of the factory by the Americans – and I looked up what was said at the time, and Lord Salisbury the prime minister – of course he didn’t comment on it for six months because it took so long for the news to get back – and then he described it as a humanitarian thing. He said, “the Africans will have grounds to thank us for having restored law and order. ” And remember, imperialism is always presented as humanitarian: the white man’s burden, the cross going round the world, the poor benighted natives, the sun never sets. . . So you have to be very careful about humanitarianism. The latest example of it is don’t give money to beggars. That would be humanitarian. You saw that in the paper? Jack Straw is spending a quarter of a million pounds telling people not to give money to beggars.

CS: That’s quite interesting. We were told on Victoria station the other day not to give money to beggars. And immediately you think, yes I want to go and give money. I immediately went and looked for a beggar.

TB: The Good Samaritan would have been arrested, given a fine on the spot, taken to the nearest cash point. . .

CS: OK, I’m puzzled about these terms. You spoke about humanitarianism and how a term such as this is used as a front for something else. . .

TB: The word is used to cover things. I don’t say that it’s always in that sense, but they do describe the bombing of Iraq as humanitarian, to protect the Kurds in the North and the Shiites in the South. I mean: “peacekeeping”. I’m interested in language. We used to call it the War Office. Then it became the Ministry of Defence. We used to talk about the hydrogen bomb, now we talk about a deterrent. And the language is very cleverly constructed to give the impression that it’s not what it is. Humanitarian Intervention. World Peace. Chomsky said the other day that whenever you hear the words “Peace Process” remember, this is what American national interest is about. You don’t want to be cynical, but you do have to understand language.

CS: There’s a lot of euphemisms used, isn’t there? I mean, Free Trade: it actually means protectionism in the United States. Globalisation actually means the concentration of power in fewer and fewer hands. The International Community means the elites within the G7. . .

TB: I know half of the International Community myself. It’s a tremendous achievement. I mean, I’ve actually met Robin Cook. (Laughs). I think that a little bit of gentle mockery is not a bad thing really. Because the odious hypocrisy of the language that they use. . . And I mean, the guys in Prague are troublemakers and thank god the police are dealing with them, but the demonstrators in Belgrade are. . . the police mustn’t fire at them. The miners in Yugoslavia striking against Milosivec are heroes, the miners in Britain striking to keep their jobs are revolutionaries. I mean the whole thing has got to the point now where unless you address the language you can’t explain to people what’s happening.

CS: The notion of Capitalism gives off this idea that we have a free market, and various institutions struggling between themselves to lower prices. I know this isn’t true. One of the things Chomsky points out is that the state is more often used to funnel public money into private hands. I was just wondering, given your wide experience of actually being in government and watching government if. . .

TB: Well Thatcher said she’d run down the state. Actually what she did was to transfer the power of the state in protecting people to protecting business against people. And the state is more powerful than it’s ever been, but it’s on the wrong side. And this theory. . . I’m doing a broadcast tomorrow actually (10th October) about a book called The Commanding Heights, which is written by two academics, celebrating the victory of what they call market forces over the state. But it’s actually a victory of market forces and the state over people. I mean, if you take the railways – I looked it up the other day – I got the House of Commons library to tell me what are the profits of the private railway companies and what are the subsidies and many of them pay the dividends out of the subsidies and run the railways at a loss. And that’s called Private Enterprise, Public Private Partnership. It’s very easy to expose now, and what I do find is that now communism is gone and people aren’t terrified that they’re going to be invaded by the Red Army tomorrow, they’re now having a chance to look at capitalism and they don’t really like it very much. Most people would like publicly owned railways, they’d like the schools to be run by elected people, don’t want private companies taking over schools, would like the Health Service to be free of PFI (Private Finance Initiative) and all that, so I feel at the moment that the tide is coming in, not in an explicit socialist way, but it a very, very powerful anti-capitalist way. Very easy to make the case against capital and people respond, they’re insecure, they’re worried, they don’t feel happy, they don’t know what it is, and that’s the duty of explanation, that’s why Chomsky is so important because he explains things so clearly.

CS: Following on from that, and talking about government, you will presumably know most of the people who are currently in government, or at least have watched some of them coming up through the ranks. . .

TB: Well I’ve only once been introduced to Gordon Brown at a New Statesman party three years ago. I know Beckett very well and I know Blair a bit and I know Mowlam, she used to work down in this basement thirty years ago as a research assistant. Jack Straw I know from way back. Who else? I don’t really know Mandelson very well except he was a press officer for the Labour Party in Walworth Road. Gordon Brown is the only one I don’t really know at all.

CS: The puzzle I have here is, what happens to people when they enter government? This is where I’m asking for your experience. The example I’d give is Peter Hain who, not so long ago was head of the anti-apartheid movement, apparently radical, who now appears to justify the bombing of Iraq. I’m not interested in individuals. The process if you like. . .

TB: Actually Peter Hain used to come and see me once a month for a year when I persuaded him to come and join the Labour Party. He was a Liberal. Well, when you get there a lot of things happen. First of all you feel you are entering a place controlled by the people and you’re sort of glad to be there. Then the Permanent Secretary says good morning Secretary of State, and then later you get on to first name terms: I know Sir John, I have a word with Sir Alan. But of course the civil service believe in a continuity of policy, and they treat you a little bit as a Maitre D’Hotel. . . . (Conversation interrupted by a phone call during which Claire Short was mentioned. ) I forget where we were now.

CS: A similar thing in a way. I was talking about what happens to people when they get into power, Claire Short being another example of someone I used think was. . . I don’t want you to speak about the person. . .

TB: Some of these people I can’t say I was altogether surprised. But then you realise they have a continuity policy, they just want you to. . . The Permanent Secretary will do a deal with you. If you do what we want you to do, we will put out to the press that you are an incredibly able Minister, and The Economist will say that people have been amazed at Mr. Jones’ ability to handle a difficult. . . That all comes from the Permanent Secretary. If you don’t do that than they’ll put out that you’re a troublesome Minister, you’re causing trouble; they’ll go straight to your department in No. 10 and tell the Prime Minister that the Secretary of State is being very difficult. And they undermine you. It’s partly ambition. They want to get on, it’s very understandable. And partly, of course, the so-called collective cabinet responsibility, where if you’re a cabinet minister you’re responsible for everything everyone does even if you didn’t know about it. So you’re sucked in that way. And I found ways of getting round this. One way of getting round collective cabinet responsibility is to make a speech saying, a lot of people are saying to me it’s time the government looked again at the question of this or that. Well they can’t complain about that because that was reported – reportage – but of course you were really building up support. Or: Looking further ahead beyond this to the fourth Labour Cabinet, we will have to consider this. . . . And it made them very, very angry. But they want you when you are there to abandon your responsibilities, your beliefs, your constituency, your party, and simply become what’s now called “on-message”. And if you step out of line – and the media particularly – they just assassinate you. The media – it’s a long time ago now – but they used to sit in the garden and ring the front door bell, there were twenty film crews and when my kids went to school they used to swear and hope they’d swear back. And really, media harassment amounts almost to political assassination. Very, very unpleasant. And that’s another factor because if you want a good press you’ve got to do what the editor of the Guardian wants, or the editor of the Independent or the Times. So there are a lot of pressures. And to stand up to them. . . . I mean I was radicalised by being a minister. That’s when I saw how the system really worked. And that is not a very usual process, but it certainly happened to me: it gave me a lot more experience, it helped me to understand where power really lay, develop strategies for undermining or changing it, and so on. But that isn’t the norm. Mr Gladstone moved to the left as he got older, and one or two other people have, but normally you swing the other way.

CS: So why would that be? Why would they normally swing the other way when faced with the realities of power?

TB: Well because the establishment rewards you, don’t they? Very, very richly. I mean if you take the four members of the SDP – Jenkins, Owen, Williams and Rogers – they all became members of the House of Lords. I mean, that really is something isn’t it? I mean if you’re a trade unionist who goes along with the government, you become Lord Murray, Lord Chappell, and a lot more weighty. Patronage is a very powerful force. (Conversation interrupted by another phone call. )

CS: I’m still puzzled. . .

TB: About why people shift?

CS: Yeah.

TB: Well I mean it’s a variety of things. First of all you start with ideas, and you’re young, you have less experience than when you’re old, you say, it’s wrong to hunt animals, or it’s wrong that people should be thrown out of work. Then you get there, they say, half a minute, if you try to tackle that you’d have this. So you face the. . . what you might call from protest to management. Now I found that very interesting and satisfying, because at least I had a little bit of power. Whereas if you’re an ordinary MP and the factory workers are made redundant, there’s nothing you can do but protest. But if you’re a minister. . . I’d say, right, I’ll do this, I’ll do that, I’ll do the other, so you could help a little bit. But of course all the pressures from the department, and from your colleagues, broadly was, oh well, that’s inevitable, it’s globalisation, you’re causing trouble, there’s nothing could be done, they’re not very representative, they don’t matter, we’ve got a lead in the polls. And then the sort of hint that if you’re a good boy you’ll get promoted and you’ll end up as Lord So-and-so. I mean, I’m putting it very crudely, but I think that is what it is. And then the media say, right, marvellous article Lord Jenkins whatever he is, in another masterly address to the nation said. . . Mr Benn in a typical article shouted. . . I mean they give government health warnings to explain who they want you to listen to. And all these pressures become very great. And also I think a lot of people are a bit overawed by civil servants. “Come and have dinner, we’ll discuss it. . . . ” The quickest way to get to the top in society probably is to be a Blair Babe now. And then all of a sudden you find you’re invited to parties. I don’t want to be cynical, because I’m not. But I’ve seen it happen to so many people who move from the left to the right so damn quickly. The number of Trots who are now Blairites. I mean, Aleister Darling was a Trot, I believe Steven Byers was a Trot, Alan Millburn was a Trot. And the Comms (Communists) shift because funnily enough the Comms identify in New Labour the very Democratic Centralism they admired in Russia. They sort of recognise it. That’s an ideological phenomenon.

CS: New Labour is a Democratically Centrally organised party these days?

TB: Absolutely the same.

CS: Going back to the globalisation thing. There’s a Zapatista slogan, “a thousand yeses and one no!” We know what’s wrong. It’s what we do about it.

TB: Oh I agree. But then that’s what you have to think about. I mean, for example, I was the Energy Minister when we were developing the North Sea. So I suddenly found myself dealing at the very top level with Esso, Amoco, Texaco, Conoco, with BP, the bloody lot. And I recognised they were bigger than Britain as companies, so I treated them like foreign powers. I’d say, we have a common interest in getting oil out of the North Sea. You’re looking after your shareholders, I’m looking after my electors. If it’s a conflict between your shareholders and my electors, I’m going to win. And one of them, the Esso guy, said, I can’t negotiate with you. I said, why not? Well, he said, your political philosophy is different to mine. So I said, right, OK, thank you very much. And you could see his own people quivering ‘cos they wanted the bloody oil. So they went away. And then a year later they asked me to lunch. So I talked him about his golf, his wife, but I wouldn’t discuss oil with him. And of course they capitulated, because they wanted the oil. I’ll give you another occasion when we discovered – at the time the Balance of Payments was a big problem – that by transfer pricing, you know what I mean. . .

CS: I don’t.

TB: Well within a company you can arrange to make a profit in one country and not in another. Well I knew that Phillip’s of Eindhoven were running a Balance of Payments deficit on Mullards and all the factories they owned here. So I got in a helicopter, went to Eindhoven, said to Mr. Phillips, if you don’t change that, I’ll tell you that the Minister of Defence will never buy another Mullard valve off you. And a year later my official came and said, by the way, Secretary of State, we’ve discovered they’ve now shifted it. So they aren’t making a Balance of Payments deficit. So that was just bullying them. And they spend millions of pounds on publicity, there’s a tiger in your tank, all this stuff, because they want good will with the host country, with the host government. So we’re much more powerful than we think. Mind you, if you annoy them, they’ve got all sorts of ways of getting at you. But this idea that we’re at the mercy of them. . . They’re very powerful. I sent you that thing on the World Trade Organisation? They’re very powerful. But we elect MPs in this system to protect you, not to administer the world on their behalf where you’re just a spectator.

CS: But isn’t this the problem, that given that Ministers tend to move to the right, that we can no longer depend on government, and given that the corporations are so closely tied in with the current administration, that those of us who aren’t ministers, who are just blokes on the street. . .

TB: If we’d have been talking about apartheid forty years ago, you’d have said the same to me about apartheid. . . The police are controlled by the whites, the media are controlled by the whites, the army’s controlled by the whites, what hope is there for change? It changes from underneath.

CS: So you would promote protest?

TB: Well I don’t like the word protest. I know what you mean of course. But I don’t regard it as protest. I regard it as the first stage of political campaigning. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard my sequence of events. When somebody comes up with a progressive idea, to begin with, you’re mad, bonkers. Then if you go on, you’re dangerous. Then there’s a pause. Then you can’t find anyone who can say they thought of it in the first place. That’s how progress is made. This is why I do believe in the vote. In the end, all these people who’ve been tempted to the right realise the warning lights in their constituency are brighter than the bright lights from No. 10 offering them things. And then they begin listening. The Poll Tax was an example. And the fuel thing is interesting, because although the people who were running it were anti-government, the support was very general. Because the fuel tax is too high. And I think now, after Prague and Seattle, maybe Belgrade even, you’re going to find a lot more of this. I mean, how did women get the vote? Mr. Asquith, the prime minister, said that if women got the vote it would undermine parliamentary democracy. How did they win? How did the Tolpuddle Martyrs get trade unionised? It’s self-organisation. That’s why the word protest is too negative. You’ve got to be in favour of something. Ban the Bomb, Votes for Women, Jobs for All, those are sound bites that mean something. They are the rallying cry, but not on a sectarian basis, I’m more socialist than you are, that is absolute dead duck sectarian politics, but issue based politics. . . The Miner’s strike attracted people from the whole political spectrum.

CS: Going back to protest. It’s the same root as the word Protestant you realise?

TB: Yes it’s very interesting isn’t it.

CS: And from Protestantism, which is protest against the Catholic Church. . .

TB: The priesthood of all believers, you see. I was brought up to believe you don’t need a bishop or a cardinal. Were you brought up in a religious home?

CS: No I wasn’t personally. But I’ve looked a lot, especially at that period, the Diggers and the Levellers, Gerard Winstanley. . .

TB: Oh yeah. I’ve got a picture on the wall over there of Daniel in the lion’s den. Have you heard that story? In the bible there’s a man called Daniel, and he went into a lion’s den. They said, you’ll be eaten up. He wasn’t. And my Dad used to say to me, dare to be a Daniel, dare to stand alone, dare to have a purpose firm, dare to let it known. An old testament story. And I found that picture in the YMCA in Nagasaki, and I took out my camera and I photographed it. So you see, there is, all the political battles we fight now were fought in the name of religion in the past. That’s why it’s so important to study religion. Martin Luther against the Pope was the same as the Campaign Group against New Labour (laughs). I didn’t know that Protestantism came from protest, because that entirely marries in with my understanding of what you’re doing. You’re challenging unaccountable power.

CS: Of course, those of us who only have the vote, that’s as far as it goes in terms of our political influence, have tended to take other means of direct action. Have you got any views on that?

TB: I’ll give you some very good examples of direct action. Monsanto. WTO. IMF. Brussels. All extra-parliamentary. Only they’re not called that. None of them were elected. And when Ford closes Dagenham, that’s direct action. So you’ve got to be clear in your mind, that governments are driven by direct action from capital. That’s discussed as “the real world”. So when they face direct action in the streets of Prague. . . Oh my god, this is a revolution. And they always try and make protest movements out to be violent. Just as Thatcher called Mandela a terrorist. Which he was I suppose. At his trial he said, we tried peacefully, then by non violent activity, and then we took to the gun. He was a terrorist. And then he wins the world peace prize and becomes president of South Africa. That’s how it happens. It’s very important not to differentiate protest from the democratic process. Because the ballot box is so important. There’s people on the left who say, the ballot box is a waste of time. Forget them. When Mandela voted for the first time at the age of 76 there was a lot of grown men, including me, wept buckets. That was what it was about. It doesn’t solve things, but it gives you the mechanism to hold to account the people with power.

CS: You spoke of sectarian problems on the left. There’s a huge history of this. This is one of the problems we encounter. If we really are to overcome the powers of capitalism then we need some sort of unity. . .

TB: Yes, but you can’t actually get it on the basis of ideology. It has to be on the issue. On the Miner’s strike, all these left groups supported it. On Seattle, they probably all supported it. On pensions. . . So I’ve long ago given up the idea that there’s a better party, with Scargill’s party: not that I ever had it, you know, I’m a Labour Party person myself. But it’s a phenomenon, a self-weakening phenomenon, self-indulgence of a kind. Although what they write is very brilliant. I mean, I read all the left press. Far from being mindless militants, they’re the most formidable intellectuals. I was talking to an Anarchist yesterday. He’s a waiter in a restaurant. He’s always been very friendly to me. He said, I was imprisoned by Franco because I was an Anarchist, and I’ve come here. He’s a good lefty, and he knew of Portillo’s father. We had a lovely talk. And Anarcho-Syndicalism is a very important strand of thought, and it’s always dismissed as just a lot of. . . Like the Luddites and the Ranters. The Ranters were actually quite sensible people, going round, teaching people. And the Luddites didn’t want to destroy the machines, they wanted to control the machines, so they destroyed the machines in order to get control. And all that’s always done. Even the word “silly”. Silly means religious. It’s either silly or daft, I forget which. . . .

CS: So do you see yourself as a religious man?

TB: I was brought up on the bible. But I’m not practicing. First of all I think that the moral basis of the teachings of Jesus – Love thy neighbour – is the basis of it all. Am I my brother’s keeper? An injury to others is an injury to all, you do not cross a picket line; and that comes from the book of Genesis and not the Kremlin. And my mother brought me up on the Old Testament, in the conflict between the Kings and the Prophets, the Kings who had power, and the Prophets who preach righteousness, and I was taught to believe in the Prophets and not the Kings. I mean, my cultural roots of Dissent and Protestantism and Non-Conformity all come from there. But it doesn’t mean I’m trying to impose my religion on anyone else, or that any of the mysteries – the virgin birth or the ascension – interest me in any way. But I think if you are going to relate to a society with arguments that make sense, you have to relate to your common cultural background. And if I say, when Cain killed Abel in the garden of Eden – am I my Brother’s keeper? – and that’s really why we don’t cross a picket line, people register. Whereas if I say, in my particular socialist sect it makes it clear that it’s a treachery to the working class to cross a picket line, they might say, oh hell, there he is, he’s at it again. So it’s partly presentational. It’s a cultural, historical, traditional presentation of that.

CS: I’ve been reading a bit of Liberation Theology recently. .

TB: Oh that’s very interesting. I’m very interested in Liberation Theology, when the priests are Marxist and the Marxists are Christians. You weren’t brought up in any religion at all?

CS: I wasn’t. Well, born in the 50s, brought up in the 60s. It was a secular state by then. I did go to a Baptist church but I didn’t much like it.

TB: Some of them are pretty restrictive in their view.

CS: Yes, I must admit, I’m not religious really. But, like you, I like the use of symbolism and imagery. I think the problem on the left is this pretence that we have a scientific world view, when in fact it’s not really scientific, it’s humanitarian. . .

TB: There was a conflict – I only learned this recently – between William Blake, who was a non-denominational Christian, and Tom Paine, who was an atheist. And Blake’s analysis, Blake believed that the origin of reason was the devil, and that faith was what mattered. Therefore he played no part whatever in political activities. He was a visionary, a prophetic voice. Whereas Paine was involved in everything. And the idea that reason owes its role to the devil: it’s totally unscientific, but there’s something in it.

CS: I think you need both, faith and reason. Which is maybe where I’m not a Christian, because Christians have faith in something that I can’t see or feel or that I don’t know much about. However, I can believe in the possibility of something, that by putting my energy into that possibility I can make it happen. That to me is belief on a concrete level. That you can believe in – say – reforming an institution, doing something about something, and actually then make it happen. I still think you need reason down the line. I think if you lose reason. . .

TB: Well you see, Christians believe that God created man, and humanists believe that man invented God. But whichever way you look at it, we’re brothers and sisters. Either we’re brothers and sisters because we’re children of God, or because we’ve banded together to invent God. So the ethics of the humanist and the ethics of some Christians are very similar. And we don’t want to create divisions between humanists and Liberation Theologians, and more than we want between the New Worker and the Trots. It’s not helpful.

CS: I’m not sure how much longer I’ve got.

TB: I find these discussions very interesting. Tell you what, I want to know all about you. How old are you?

CS: 47. I’ve been a single parent. My son’s now 20. He’s now got himself a flat on his own. He’s left me.

TB: What have you done all your life?

CS: Bits and pieces, really. Bit of a drifter, I suppose. I’ve done lots and lots of jobs. Active in the Labour Party for a while. Briefly. I left the Labour Party over the Poll Tax, because they said we had to pay the Poll Tax and that then they’d get in and repeal it. But if we hadn’t actively fought against the Poll Tax, the Poll Tax would still be here wouldn’t it?

TB: Well Kinnock was furious with me. I didn’t pay the Poll Tax till the abolition was announced. I wouldn’t tell anyone else not to pay because they would be taking a risk I wasn’t taking. Yes, the Poll Tax was very important. The other fairly non-political example was when Hamilton killed those kids in Dunblane. Public opinion was so strong even Michael Howard had to ban handguns. The last thing he ever thought of. But he had to do it. And public opinion: protest formulates public opinion, and Parliament is the last place to get the message. At the moment it’s so totally out of touch, I’m not sure it’s getting any messages at all. As we approach polling day one or two messages will be conveyed, through MPs who’ve got to fight their seats. And it’s very interesting to see how the process works. And I think to understand how the democratic process works is the most important thing, so people don’t get frightened by it, and get put off, and give up. But being in the Labour Party is a very minor matter in that sense. You can do all that you want to without being in the Labour Party. And I’m giving up because I want to spend more time on politics.

CS: yes, I’ve heard this quote. What did you mean by this?

TB: I meant I don’t want to stand night after night on a three-line whip about cutting benefits for lone parents, putting in tuition fees, ending jury service, broadening (the definition of) terrorism, fining yobs at the nearest cash-point, going to war with Kosovo. I don’t want to do it. And I’m free. I’m a free man now. It’s lovely to be old. I’ve got age, experience and zero personal ambition. No body could corrupt me by anything: possibly a job in the government, a peerage, a quango, I don’t want any of it.

CS: So how do you see the next few years then?

TB: Well come back on my hundredth birthday and I’ll tell you. But it’s the beginning, I think, of a very exciting period of political work. Maybe. . . I mean you do need the media to get your case across. I can’t complain because I get lots of opportunities. Maybe when I’m not in parliament they won’t, I don’t know. It doesn’t matter what happens to me, but I would like to have access to the public and at the moment I’m very, very lucky. I had a business man this morning, from the London Business Magazine come to interview me. And you come and talk to me, and the BBC come and ask me questions. I really am a sort of wholly untrained guru who sits at home and meets people and tries to answer their questions. Very, very enjoyable.

CS: Talking about political parties, since the rise of New Labour I have felt disenfranchised. There is no longer a party that represents me and my views. I’ve heard you refer to New Labour as a coup d’etat on the Labour Party. . .

TB: Yes, it’s s new political party. I’m not a member of it. It’s probably the smallest political party in the history of British Politics, but they’re all in the cabinet so it makes it quite powerful. They’ve captured the MillbankTower. They would really like a coalition, I think. If you talk privately, they’d like Ken Clark and Charles Kennedy in the coalition and have a one-party state. All the guys at the top huddling together to see that people like you never have any influence. I think that’s what they’re really about. And then Scargill made the same mistake in setting up the Socialist Labour Party. When I saw Blair a few months ago I said, you and Scargill have made the same mistake, you’ve set up a new political party. He looked a bit sort of quizzical. But they have.

CS: Except that Blair has power and Scargill doesn’t.

TB: Yes, but I mean, they both left the Labour Party. And yet he needs the Labour Party. As we get near polling day you wait and see. Even the Brighton Conference had a touch of old Labour about it. And the unions beat him on pensions: a very important victory.

CS: And following on from that, Ken Livingstone’s victory in London: it wasn’t just because everybody liked Ken, it’s because he was opposing the privatisation of the tube. Opposed to the PFI (Private Finance Initiative).

TB: And also proved to people you don’t have to be Tony Blair to win. That was the really important point. Because Blair had been saying, well drop me if you like, but you’ll lose. And Ken said, sorry, you can throw me out, but I’ll win. And he did.

CS: But then you see the anti-democratic tendencies of New Labour. That despite the fact that this was really a referendum on PFI , they still continue with PFI. That is, they are ignoring the will of the people.

TB: Yes but you have to take a moving picture in politics, not snapshots. I think of all the things I’ve campaigned on in my life, years and years ago. Gay rights. I introduced a bill in 1989 for an equal age of consent. It was laughed at. Now law. I campaigned for the end of apartheid. Everybody said it will never happen. I’m not saying I did it. You anticipated it. And the PFI will go down the pan because the unions won’t have it. And the unions are beginning to feel their muscle again. They wanted Labour to win, quite rightly after the Tories, they want Labour to win again, quite rightly, and there are a few peerages hovering over the heads of the General Secretaries. I wouldn’t be surprised if all the principle General Secretaries don’t take up with Mr. Blair’s reformed House of Lords. There are a lot of factors at work. But underneath, where people are people, it’s not going to quite be like that.

CS: So you remain an optimist then?

TB: Oh yeah.

Related Posts

- Let’s have Tony Benn’s Democratic Revolution now.

- Big Ideas that changed the world – Democracy – Tony Benn

- Thoughts inspired by Tony Benn

- The Issue was Thatcher but it might as well be now

- The Case for Socialism

- Tony Benn and the idea of Participation

- Privatisation of the NHS, Tony Benn and how to stop the protests

- Socialism returns to mainstream politics